Bleeding Trees in European Art

The artists Giovanni Bellini and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes both picture worlds in which trees are bloodied by human action, but to very different ends

European art has a history of tree iconography. Dead trees, for example, have a longue durée as symbols of mortality. From Venetian artist Jacopo Bellini’s fifteenth-century notebooks, in which dead trees and stumps foreshadow the death of Christ, to French Rococo artist Antoine Watteau’s placement of decaying, fallen tree in the foreground of Watteau’s The Pilgrimage of Cythera (1717), trees visually communicate the shift from life to death, the passage of time, and memory.

I want to consider the meaning-making potential of a particular aspect of this motif—bleeding trees—in two examples from different contexts within Western art: Giovanni Bellini’s The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr (c.1505-1507) and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes’s The Aftermath of War (c.1870s). While these works emerge from very different historic and artistic circumstances, in both images, trees bleed due to human antagonism. In these paintings, trees are more than iconographical signs. The trees are victims of human violence, yet they are pictured with a fundamental, physiological connection to the human body—they bleed. What message, then, do these injured trees send?

Trees, Blood, and Bellini

The Venetian Renaissance painter Giovanni Bellini created the subtly brutal devotional paintingThe Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr in around 1505. It depicts the assassination and martyrdom of 13th-century Dominican friar Peter of Verona, or Peter Martyr. His assailant, Carino of Balsamo, plunges a sword into his chest as he collapses, having already lodged a billhook (a pruning instrument) in his head. Carino would later repent for the murder and become a Dominican himself. An attack is levied on Peter’s companion by a second assassin.

Bellini filled the scene with rural characters who are seemingly unaware of the murders taking place in front of them. Swinging axes, laborers chop wood and clear brush in a thicket of trees. The artist rendered the trees sensitively, with careful delineation of individual leaves and slender trunks that are almost the same scale as the human figures.

Bellini fashions a clear parallel between the woodcutters and the assassins. Both are in motion and enact violence through their respective implements. The pose of Carino, who hunches over his saintly victim, is repeated in the white-clad laborer directly behind him. The pose of the woodcutter in blue, who raises his axe above his head and bends at the knees, mimics that of the second assassin. The trees, therefore, become a metaphor for the body of Peter.

Bellini, a master of nuanced interplay between human figures and the environment, reinforced this metaphor through the subtle presence of blood. Where the woodsmen strike, a red gash appears. These bloody wounds are echoed in Peter, whose blood runs down the knife protruding from his head and drips onto the ground.

Bellini’s inclusion of trees, woodcutters, and blood is more than a clever visual metaphor. We can see it as a reflection of both Venetian ecological attitudes and the iconography and spiritual narratives that surround Peter Martyr. Trees were highly valued natural resources and were often at the center of Venetian environmental anxieties during the fifteenth century. Woodcutting and trees (specifically, bleeding trees) were also closely tied to legends and attributes of the saint. Rather than remaining separate themes, however, the trees’ dual function as a spiritual and natural resource creates a religious and environmental confluence; the ecological undertones of The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr augment its spiritual content.

Trees provided integral resources in the centuries surrounding the creation of Bellini’s painting. The preindustrial age was what Karl Appuhn calls an “era of wood.”1 Forests and their products formed the backbone of society; they provided building materials for shelters, cities, and boats, all sorts of food and fodder for animals, fuel, and heat. Venice itself rests on thousands and thousands of felled trees, which support the city from sinking into the lagoon. As a commercial center, the city was one of the largest wood-based fuel consumers in Europe. In addition to economic power, trees afforded Venetians their political power, as their fleet was almost entirely built from wood from the mainland.

In the decades leading up to Bellini’s 1505 Assassination painting, Venice’s reliance on the natural world was becoming more apparent to its citizens. Throughout the fifteenth century, silting of the city’s canals and ports, as well as rivers of the mainland, caused public anxiety about environmental change.2 This anxiety extended to wood supplies as well, with constant fears about the lack of fuel and building materials. Direct state control of mainland forests began in the 1470s, with legislation establishing major forest reserves. Large swathes of the mainland’s oak, beech, and fir forests were held for the shipbuilding, while smaller forests of other kinds of trees were reserved for firewood.

Bellini’s inclusion of woodcutters speaks to the dependent relationship between Venetians and trees, entangling environmental concerns with religious devotion. As a spiritual image, the viewer was meant to dwell on the sanctity of Peter Martyr. This sanctity is in part displayed by the posing of the figures. Peter gracefully collapses with his face, arranged in a peaceful expression, raised to the heavens. He does not try to escape but, as a dutiful martyr, accepts his fate. Bellini treats Peter’s companion, a fellow Dominican, as a foil to Peter’s composure—this figure runs from his attacker and looks back in fear.

What’s more, the artist drew upon legends of the saint that explicitly implicate bleeding trees. A contemporary account of the saint’s life describes a posthumous miracle credited to Peter Martyr:

After Blessed Peter Martyr was canonized and his feast had been solemnly celebrated in Milan, a certain believer of the heretics sent his servant boy into the woods in order to burn them down. The boy, fearing his lord, went to do the task, asking the Lord Jesus Christ that for the honor the Saint to whom his lord wished to do injury, He would deign to accomplish some miracle. When he was about to burn the oak, having taken up the axe, from the first cut blood began to flow copiously, so that the iron and the handle and his hands and a great quantity of earth was reddened with blood. Then crying out, he immediately returned, and faithfully related what had taken place. Many ran back with the lord, and truly saw the miracle of Blessed Peter Martyr and had great devotion.3

Bellini adapted this passage in multiple ways. Subverting the original chronology of events, he placed the posthumous miracle in the moment of Peter’s death. The character of the servant boy becomes multiple woodcutters, who appear to be laborers by trade rather than servants. In the account, the bleeding trees create a spectacle that attracts the attention of many. Bellini’s bleeding trees, however, seem to go unnoticed in his depiction. Finally, the amount of blood is significantly reduced. Rather than “copious” amounts of blood pouring from the cut tree, Bellini chose to subtly suggest blood with small slashes of red paint. The muted qualities of The Assassination can be credited to Bellini’s preference for intimate, meditative scenes. Rather than presenting the subject matter in a lurid or obvious fashion, the artist instead creates personal engagement through allusion.

Canonization documents from Pope Innocent IV also provided the details of the attack that inspired Bellini: “[Carino] crudely attacked the holy head with a sword, and left horrible wounds on it, with the weapon sated with blood of the just, that man to be venerated, not turning from the enemy, but immediately showed himself like an offering.”4

The Assassination of Saint Peter Martyr draws on both the ecological context of Venice and the textual sources of the saint. In both spheres of meaning, trees play a key role. Recognized as vital resources, trees were valued by Venetians during a time of environmental change and degradation. Within the sources that Bellini used for this work, trees are subject to miracles and are used as a metaphor for the body of Peter.

Beyond references to the saint’s attributes and miracles, trees and the natural world are linked to divinity more generally in The Assassination. A ray of light cuts through the center of the grove. Comparing this ray with the reflection on Carino’s helmet and the shadows of the figures, it is clear that Bellini created two light sources: the light of the natural world and the light of the divine. This divine light, rather than shining on Peter, treats the trees and woodcutters with its spiritual power instead.

These environmental and spiritual themes are thus linked. In The Assassination, the trees become tangled in the meditative and devotional qualities of Peter. Not only do they act as a metaphor for the saint’s body, but they also reflect the sacrificial nature of Peter’s martyrdom. In his canonization bull, Peter is described as an “offering.” This of course invokes the sacrifice of Christ, but through the lens of Venetian environmental anxiety and The Assassination, a parallel can be made to the sacrifice of natural resources for societal use. Like Peter, who accepts his death with stillness, the trees must receive the blows of the woodsmen. Bellini acknowledges their saintly sacrifice by illuminating them with holy light. The woodsmen, like Carino, the assassin-turned-saint, are simultaneously villains and protagonists. They cut down the valued trees violently, but in the process, provide life-sustaining resources. Carino, too, cuts down Peter. Peter’s death, like the destruction of trees, ultimately served a higher purpose. For the trees, supporting the city of Venice. For Peter, spiritual fulfillment.

Puvis de Chavannes and The Aftermath of War

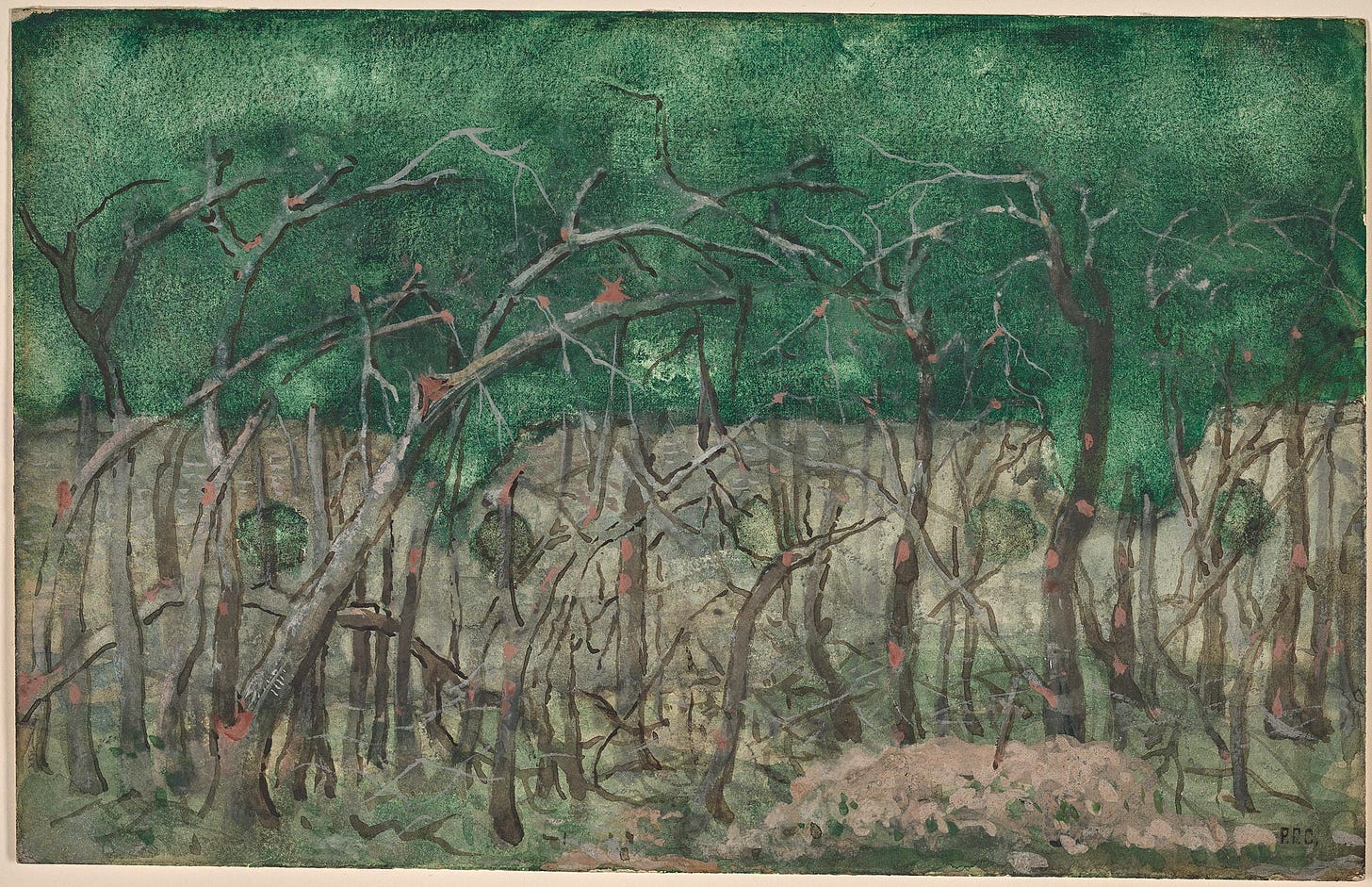

The Aftermath of War by French painter Puvis de Chavannes (who was a celebrated muralist associated with both classicism and symbolist art) is very different from Bellini’s painting in medium and context. Instead of an oil painting on wood, Puvis used watercolor on paper; instead of a devotional image made for a patron, the artist created a lurid work intended for his own processing of violence. Gray trees, with terracotta smears suggesting bloody wounds, stand in front of a sickly green sky and a wall-like structure. No human figures are present. The fighting has either ended or moved on, leaving only arboreal damage behind.

Puvis was responding to the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871). Having fled Paris due to the conflict, the artist was acutely affected. The Morgan Library describes this watercolor as “an impenetrable and damaged landscape as a manifestation of anguish.” The anguish is the artist’s. Yet, the bleeding trees suggest the material, not just symbolic or individual, impact of conflict. The artist’s loose, drip-like handling of rust-colored pigment evokes real blood, not just its illusionistic representation. Also, trees can, in fact, “bleed” when injured.

Puvis, while creating a symbolic, personal landscape, also visualizes the idea that war harms not just people, but other living beings.

Looking at the military and environmental history of the Franco-Prussian War, there are indeed instances of battles being fought in woods. The pivotal Battle of Sedan, in which the Germans defeated French forces and led to the overthrow of the Third Empire, involved the French retreating into the bois de la Garenne. A first-hand account describes the terrain of Sedan as “rugged” and dotted with trees: “Ce terrain est tourmenté, coupé d'un grand bois, de bouquets d'arbres, de haies, de murs de clôture, de maisons, etc... Au centre est le bois de la Garenne” [“This land is rugged, interspersed with a large wood, clumps of trees, hedges, boundary walls, houses, etc… At the center is the Garenne woods”].5

I’m not suggesting that Puvis’s watercolor is a literal illustration of this event. But, I do think we can consider it an implicit acknowledgement of the material, environmental toll of human conflict, and as a conflation between the artist’s mental anguish and the physical trauma to plant life.

Contrasting the function of bleeding trees in the paintings of Bellini and Puvis produces very different visions of environmental management (or rather, in the case of Puvis, mismanagement). In The Assassination of Peter Martyr, the felling of trees is a necessary sacrifice and is treated with a spiritual reverence. In The Aftermath of War, the injuring of trees is tragic, purposeless, and a result of human folly. Both, however, picture a fundamental material relationship between the arboreal and the human, and pose a question of environmental ethics: when does human intervention in the natural world help us, and when does it hurt us?

Karl Appuhn, A Forest on the Sea: Environmental Expertise in Renaissance Venice (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 5.

Elisabeth Crouzet-Pavan, “Toward an Ecological Understanding of the Myth of Venice,” in Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, 1297-1797, edited by John Jeffries Martin and Dennis Romano (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 51.

Donald Prudlo, The Martyred Inquisitor: The Life and Cult of Peter of Verona (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008), 233.

“Bull “Magnis et Crebis,” Innocent IV, 25 March 1253,” in Prudlo, The Martyred Inquisitor, 193. In addition to providing the details of Peter’s martyrdom, the bull also contains many allusions to the natural world. At the time of the saint’s martyrdom, the “earth itself was not silent, sweating with the sprinkling of blood, the very ground resounded to the noble King concerning the warrior.” The blood of Peter is equivocated with the blood of Chris and described in natural metaphors: “A new fluid flows into the kingly chalice from the vineyard of the Church; since it was pruned by the sword of the enemy, a fruitful vine branch has sprouted forth, because it has been firmly grafted to the living Vine.” Perhaps the language here (“pruned by the sword of the enemy”) contributed to depictions of a billhook, a pruning tool, being used to attack Peter.

Emmanuel-Félix de Wimpffen, Sedan (Paris: A. Lacroix, Verboechhoven et Cie, 1871), 155. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6461612d.